There are a number of rock art sites in this part of Val Camonica

Between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries, Capo di Ponte was known as the hamlet of Cemmo—part of the priory of San Salvatore of Tezze.

In 1315 the Imesigo marsh, on the plain between Capo di Ponte and Sellero, was flooded by the River Re.

On 14 October 1336 the Bishop of Brescia, Jacopo de Atti, invested iure feuds[clarification needed] for a tenth of the rights in the territories of Incudine, Cortenedolo, Mù, Cemmo, Zero, Viviano and Capo di Ponte to Maffeo Giroldo Botelli of Nadro.

In 1698 Father Gregorio Brunelli says that the village of Zero (or Serio), which stood on banks of the River Re, east of the country today, was swept away by a flood.

After the fall of the Republic of Venice the "comune of Capo di Ponte" (1797–1798) was founded, later becoming "comune of Cemmo and Capo di Ponte" (1798 to 1815). Under the Lombardo-Veneto kingdom, the name was again changed to "comune di Capo di Ponte e Cemmo" (1816 to 1859). It has been known as Capo di Ponte since 1859.

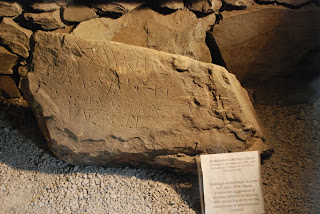

The stone carvings of Val Camonica constitute one of the largest collections of prehistoric petroglyphs in the world.[1] The collection was recognized by Unesco in 1979 and was Italy's first recognized World Heritage Site. Unesco has formally recognized more than 140,000 figures and symbols,[1] but new discoveries have increased the number of catalogued incisions to between 200,000[ and 300,000.[3] The petroglyphs are spread on all surfaces of the valley, but concentrated in the areas of Darfo Boario Terme, Capo di Ponte, Nadro, Cimbergo andPaspardo

Many of the incisions were made over a time period of eight thousand years preceding the Iron Age (1st millennium BC),[2] while petroglyphs of the last period are attributed to the people of Camunni, mentioned by Latin sources. The petroglyph tradition does not end abruptly. Engravings have been identified (although in very small number; not comparable with the great prehistoric activity) from the Roman period, medieval period and are possibly even contemporary, up to the 19th century.[1][3] Most of the cuts have been made using the "martellina" technique and lesser numbers obtained through graffiti.[2]

The figures are sometimes simply superimposed without apparent order. Others instead appear to have a logical relationship between them; for example, a picture of a religious rite or a hunting scene or fight. This approach explains the scheme of images, each of which is an ideogram that is not the real object, but its "idea".[2] Their function pertains to celebratory rituals: commemorative, initiatory and propitiatory; first in the field of religion, then later even secular, which were held on special occasions, either single or recurrent.[3] Among the most notorious symbols found in Valcamonica is the so-called "Rosa camuna" (Camunian rose), which was adopted as the official symbol of the region of Lombardy.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment